Large Language Models

This is a paper submitted for the class AIML420 at Vic in June of 2023. I like the way it turned out. It gives a pretty good snapshot of where LLM where at that time. (pdf version.)

Introduction

Large language models (LLMs) have exploded in the past year, reaching a level of fluency that seemed far off a short time ago. The most advanced models can write code, summarize and translate documents, and pass legal and medical exams. They also “hallucinate”, convincingly fabricating untrue but seemingly factual information. They threaten to empower scammers, turbocharge disinformation, and eliminate jobs. Some worry about an unstoppable arms race toward ever more powerful AIs that will come to pose an existential risk to humanity.

The key factor that enables the surprising talents of the latest generation of models is massive scale. Training runs consume tens of millions of dollars in compute time and leverage enormous datasets. But the resulting pretrained models learn generalizable capabilities that allow them to perform a wide variety of tasks.

The advances in linguistic proficiency are impressive, but are at risk of being overshadowed by big questions about the effects these models will have on the economy and society. The largest models have an unnerving level of understanding and show signs of reasoning. In training machines to use language, what else has come along for the ride?

How do LLMs work?

What is a language model?

To begin to understand how LLMs work, let’s start by defining the language modeling task. A language model learns a probability distribution over strings in a language - sequences of tokens, where tokens can be words, parts of words, punctuation, or digits. “Have a nice day!” is a fairly likely bit of English while ungrammatical nonsense like, “Nice a verisimilitude have” is improbable. Large language models train on the task of predicting the next token given some context, in other words, playing fill in the blank.

The model performs next token prediction by sampling from the probability distribution learned during training conditioned on the prompt and the sequence of previously generated tokens. A pretrained language model \(p_{\theta}\) with parameters \(θ\) assigns a probability to a sequence of tokens \(x\) as the product of conditional probabilities of each token:

\[p_{\theta}(x) = \prod_{i=1}^{n} p_{\theta}(x[i]|x[1 \ldots i]])\]Attention

Attention helps untangle context dependence in human language. Words have different meanings or “senses” depending on surrounding words. Correct grammar depends on the relations of pronouns and their referents and verb conjugation to reflect tense, plurality, or gender. Successful models of human language need to consider related words that are sometimes far apart.

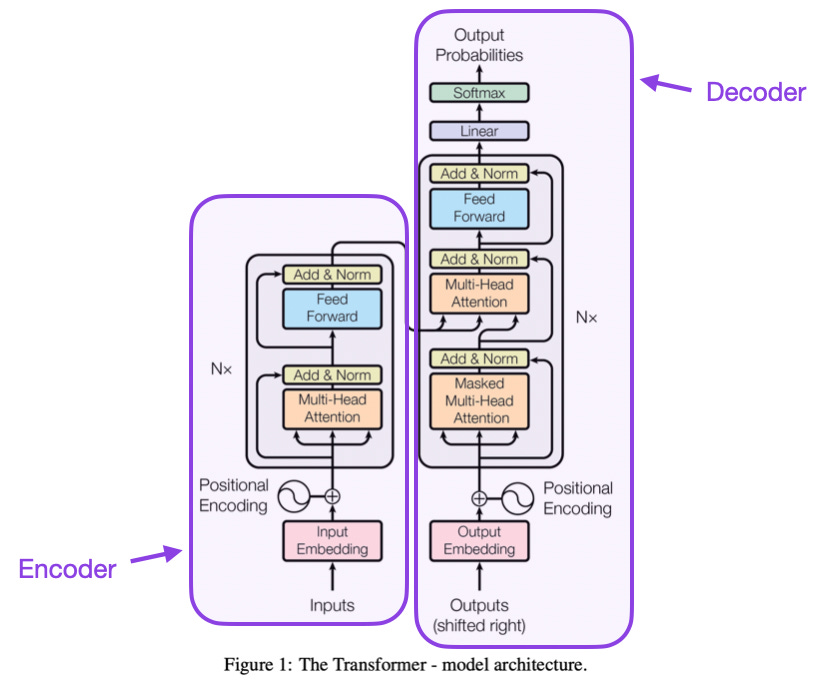

Attention gives a neural network the ability to learn these relations between possibly distant words. The present wave of natural language processing (NLP) kicked off with the paper Attention Is All You Need (Vaswani et al, 2017) which introduced transformer architecture and a specific attention mechanism called multi-headed self-attention.

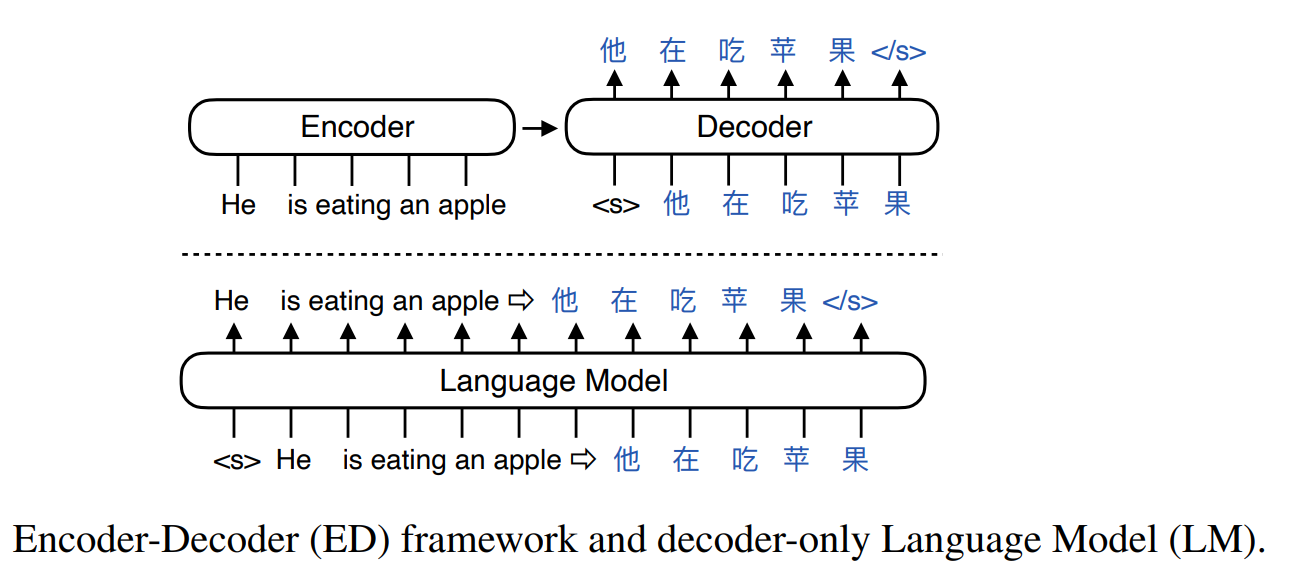

Like other sequence-to-sequence models, the original transformer architecture has two parts, an encoder and a decoder, which can be used separately. Current state-of-the-art models, like GPT, PaLM, and Llama are decoder-only autoregressive models meaning that each output token generated becomes part of the context for the next.

A key advantage of transformers over their predecessors - recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and long-short term memory (LSTM) networks - is that training can be parallelized, enabling larger models trained on more documents.

Self-supervised pretraining and transfer learning

The scale of modern LLMs would be impossible if training was bottlenecked by a limited supply of labeled data. Self-supervised pretraining solves that problem (Brown et al. 2020). The beauty of next token prediction is that the correct label is right there in the document - no human labeling required. Training data can be drawn from giant crawls of the Internet and huge archives of books and scientific papers. Self-supervised learning helps pretrained models scale. Their generizability is an example of transfer learning (Ruder et al. 2019).

The success of transfer learning in computer vision stoked hopes that it could also work for natural language. Transfer learning works because the layers of a deep neural network learn to recognize increasingly complex feature representations. In vision models, initial layers react to low-level features like edges or textures. Subsequent layers take the previous layer’s features and use them to build higher-level features. For example, two edges coming to a point and a furry texture might be recognized as a cat ear. These features can inform a variety of downstream tasks, the property of generality. As in vision, language has structure. Once learned, that structure can be applied to across tasks.

Stages of training

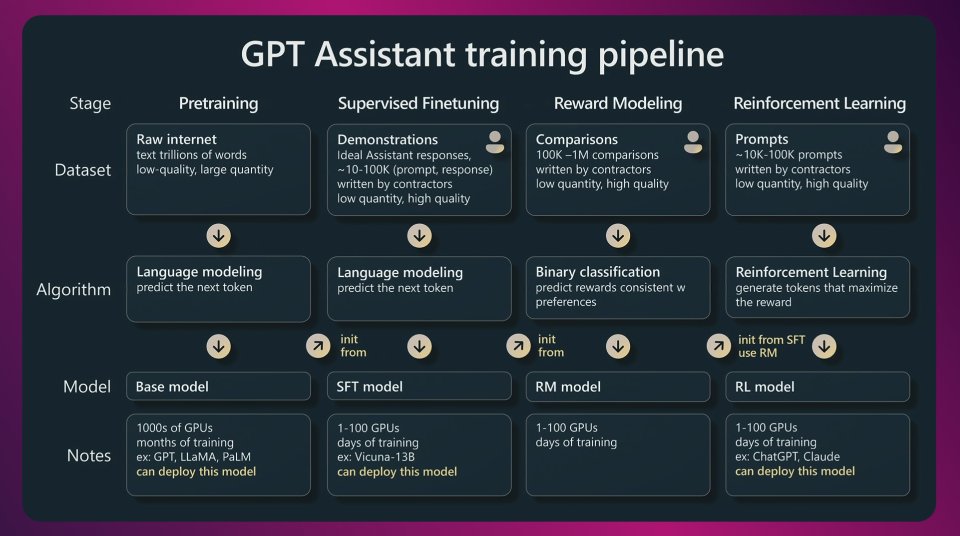

Modern LLMs are trained in stages. The vast majority of the training budget goes to pretraining on next token completion on a massive corpus of unlabeled text. This produces a base model. The next steps vary, but pretraining is often followed by supervised fine tuning for a particular use case or application domain, for example code generation or medical records. The datasets at this stage are much smaller but are human labeled and hand-picked for quality and relevance.

A model trained to complete documents doesn’t automatically answer questions, follow instructions, or obey the rules of polite conversation. Adjusting the model to follow these expectations is called alignment and can be accomplished by reinforcement learning with human feedback (RLHF) (Ouyang et al. 2022). In RLHF, the model generates multiple completions to the same prompt and human reviewers rank those completions. A reward model is trained on the rankings and then used to adjust the loss function, penalizing or rewarding completions depending on how they rank. The weighted loss then gets back-propagated as usual.

Returns of scale

Transformers and self-supervised learning, along with the engineering capacity of cloud providers, have enabled models to scale by orders of magnitude in just a few years. As of 2023, the most capable models for which numbers are publicly available have tens or hundreds of billions of parameters. Unconfirmed rumor puts GPT-4 at 1 trillion parameters, though OpenAI is not forthcoming with exact details.

| Model | Year | Parameters | Training Tokens | Context Window |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T5 | 2019 | 11B | 156B | 512 |

| GPT-3 | 2022 | 175B | 300B | 2k |

| GPT-4 | 2023 | † 1T | ? | 8k/32k |

| PaLM | 2022 | 540B | 780B | 2k |

| PaLM 2 | 2023 | † 340B | † 3.6T | 8k |

| Chinchilla | 2022 | 70B | 1.4T | 2k |

| LLaMa | 2023 | 7-65B | 1.0-1.4T | 2k |

(† unconfirmed)

A few years ago, with models on the order of 1 billion parameters, it wasn’t obvious that further scale would keep producing gains. Many expected diminishing returns to set in. Text is, after all, a limited window through which to observe the world. True understanding, it was thought, would remain out of reach without “grounding” in physical reality. Instead, scale has continued to pay off.

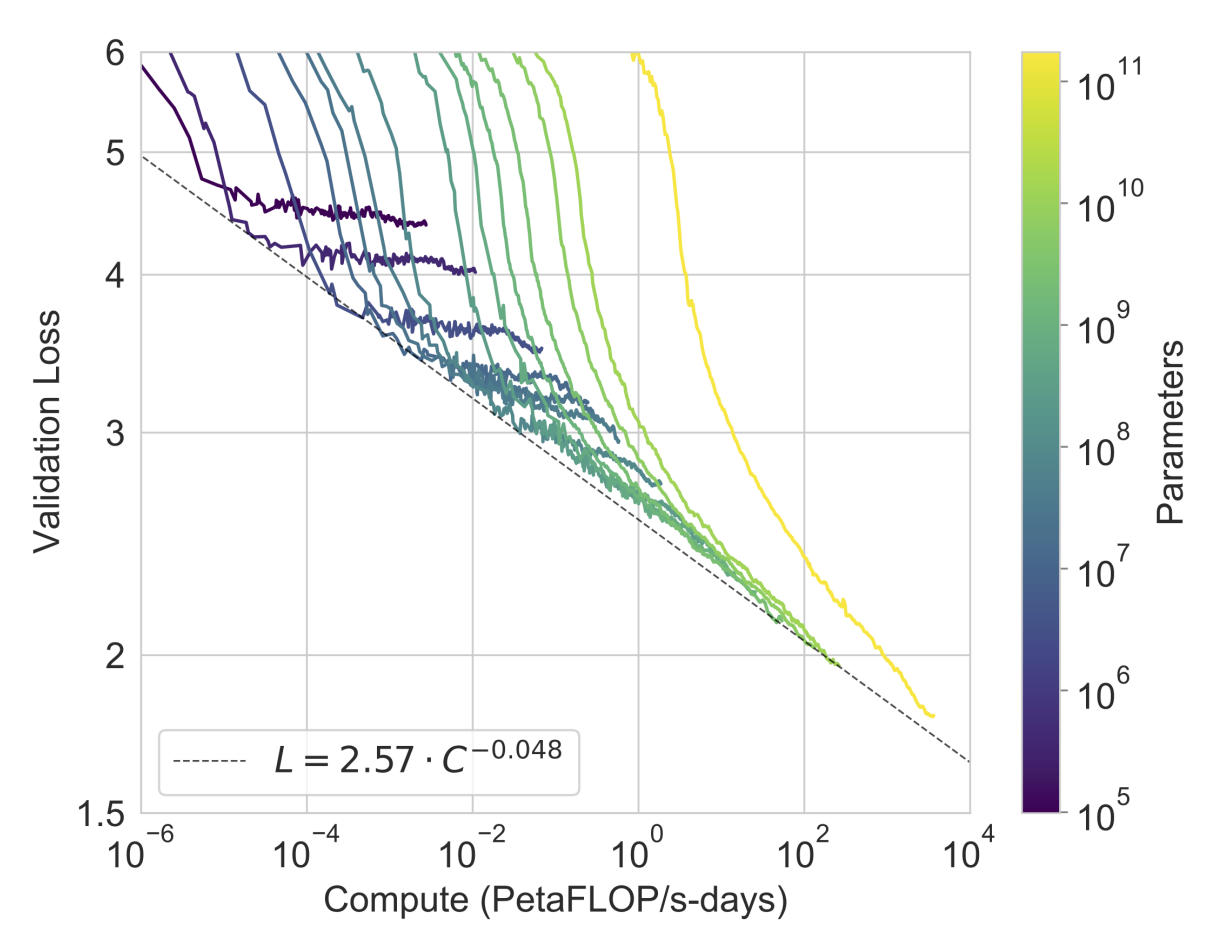

Within model families, performance scales smoothly through several orders of magnitude in a power-law relationship with model size, data size, and compute budget. For example, the GPT-3 paper (Brown et al. 2020) shows a plot of validation loss versus compute, with elbow points neatly lining up. (Figure 4)

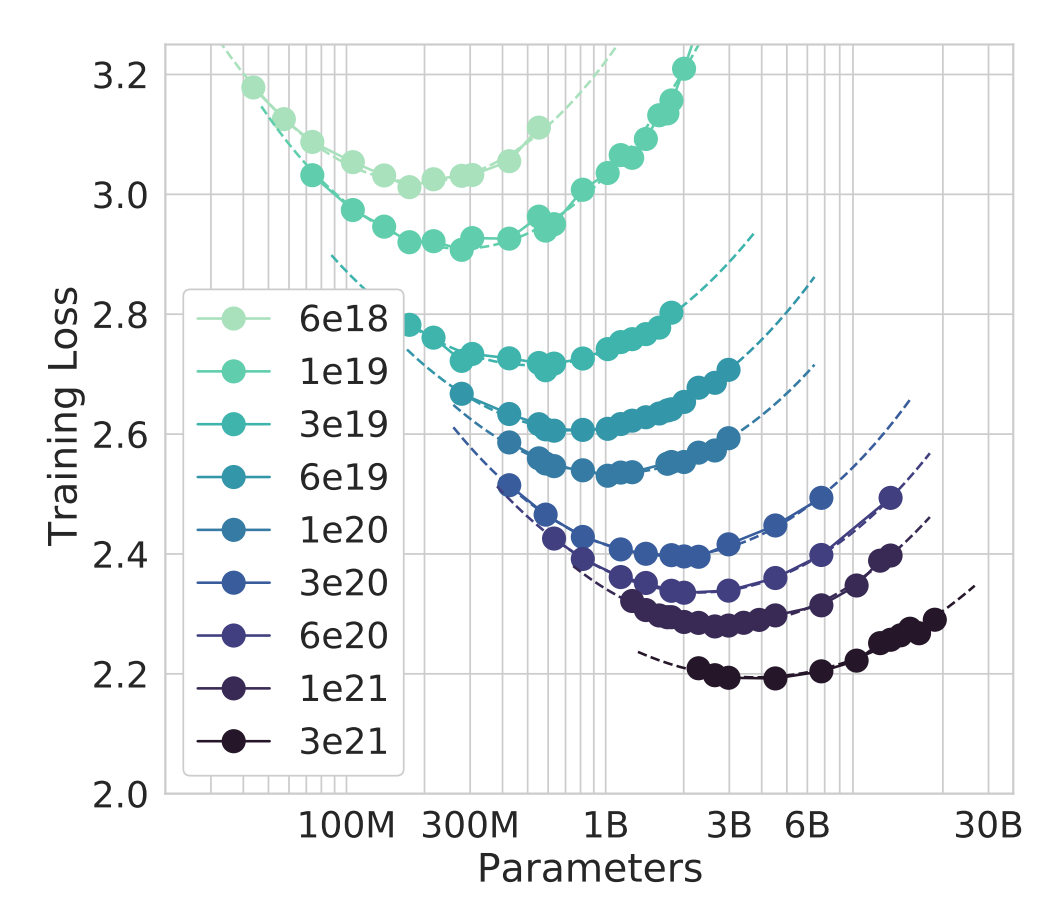

The Chinchilla paper (Hoffmann et al. 2022) reanalyzed the trade-off between model size and training data, arguing that the optimal balance for a given compute budget favored data more heavily than previously thought (Kaplan et al. 2020). This paper contains a plot of loss curves on varying model sizes for a fixed compute budget. The valley of lowest loss shows the optimal trade-off. (Figure 5)

It’s worth noting that GPT-4 is multimodal in that it can take images and text as input. After all, the amount of quality text is finite and the world is richer when you have more senses. What might we expect from foundation models that are equally facile with text, images, audio and video? (Yang et al. 2023)

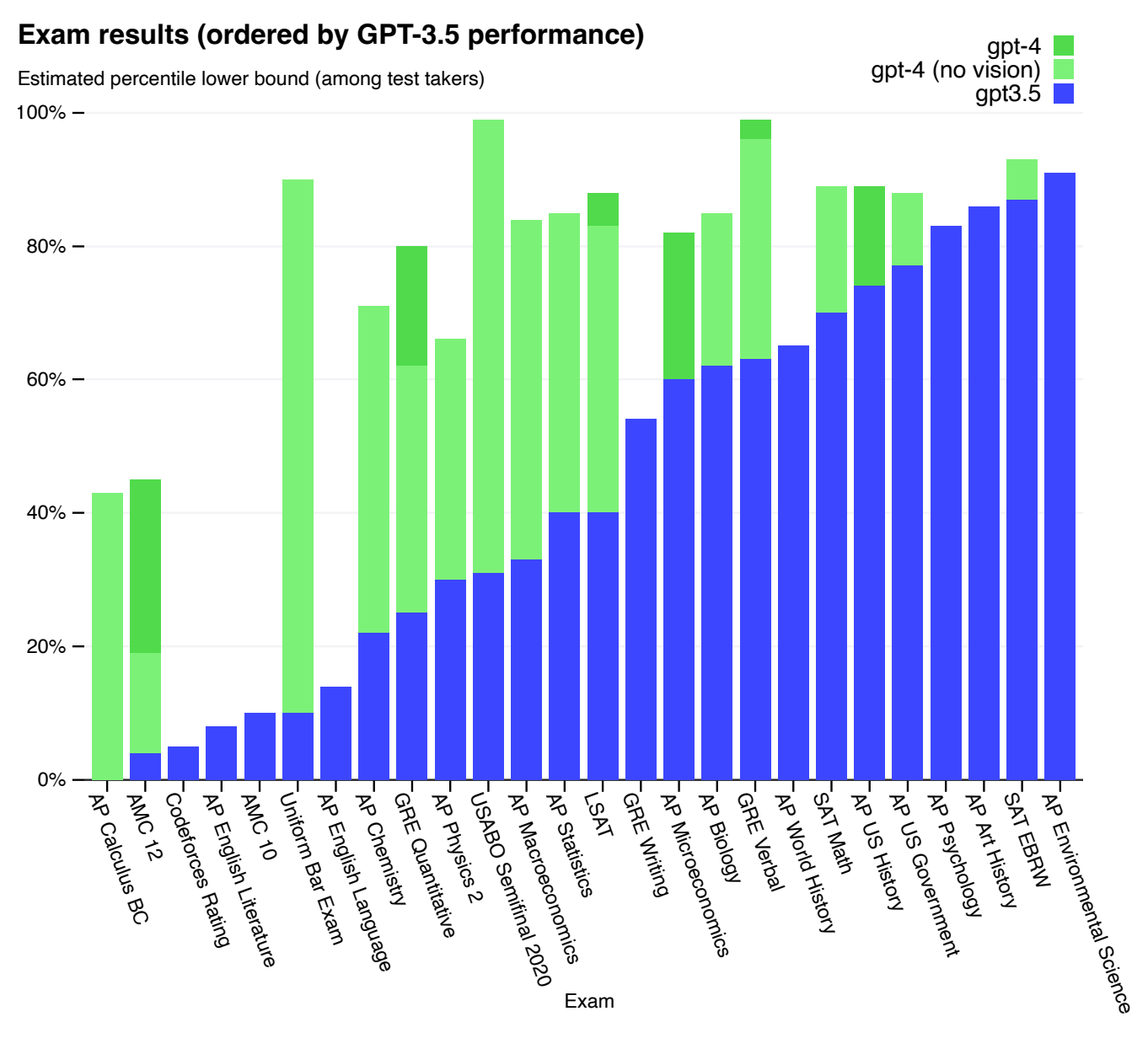

Capabilities

As designed, LLMs have an impressive facility with language. Generating meaningful and grammatical text is what they are trained for. As models grow in complexity, they acquire surprising new skills, the so called ‘emergent abilities’ (Wei, Tay, et al. 2022). They hold large bodies of factual knowledge, hallucinations notwithstanding. They can perform arithmetic, albeit clumsily and solve mathematical word problems. They can answer questions with well-reasoned arguments and self-correct when asked to reconsider. GPT-4 achieved impressive results on a battery of academic and professional exams. (Figure 6) (OpenAI 2023)

Relevant to the future employment prospects of human programmers, LLMs can generate decent code from natural language descriptions, complete with comments and tests. Interestingly, they can answer questions about existing code, showing conceptual understanding. They can also trace code execution maintaining internal state to represent variable bindings and the state of a call stack. (Bubeck et al. 2023) Todays budding programmers would be well advised to practice working in tandem with LLMs so as to be complementary rather than in direct competition with them.

It’s not at all obvious that training on next token completion would lead to models than can pass exams and coding interviews. It’s important to note that even the top LLMs often get things wrong. Even so, in large language models, quantity seems to have a quality all its own.

Ilya Sutskever, one of the creators of the GPT models, offers a simple but deep explanation. (Sutskever and Huang 2023) “The better a neural network can predict the next word in text, the better it understands it.” Sutskever suggests considering the final page of a detective novel. After chapters filled with clues and plot twists, the detective prepares to reveal the guilty party, saying, “That person’s name is…” Predicting that next word requires reasoning well beyond grammar and word frequency.

Augmented models

Where LLMs fall short, one strategy is to augment models with tools. Microsoft’s Bing AI is essentially GPT-4 augmented with search and retrieval. Rather than recalling facts stored in model parameters, risking hallucination, the model searches and summarizes the results for the user. LLMs have successfully learned to use calculators, command shells, and the Python interpreter.

Giving the model access to make API calls enables it to act in the world as an agent. In future systems, one may imagine LLMs integrated into larger systems executing complex workflows. At this point, doing so without close human supervision seems unwise.

Prompt engineering

Users of generative models have developed libraries of prompting strategies that elicit desired results, a trend that got started in diffusion models for image generation like Midjourney and quickly migrated to LLMs.

The simplest of these strategies is to give examples. The terms “zero-shot”, “one-shot”, and “few-shot” denote that the model is given no examples, one or several examples in the prompt before posing the question. Examples improve performance markedly which shows the model’s ability to learn inductively in-context. (Brown et al. 2020)

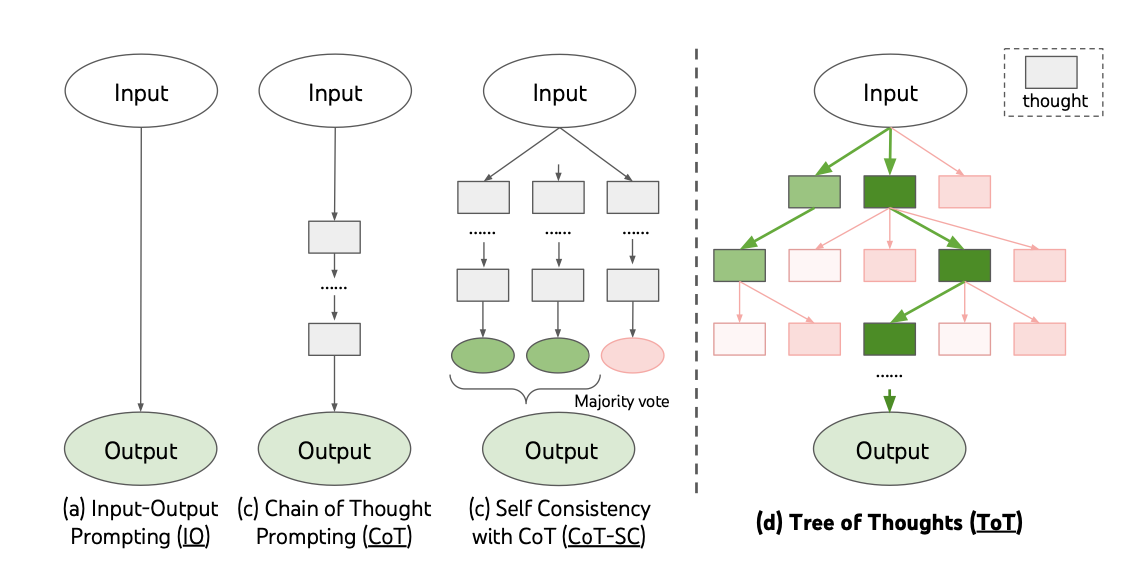

Chain-of-thought is a prompting technique in which we ask the model to show its reasoning step-by-step before giving an answer. Like few-shot prompting, examples are given. But these examples include explicit descriptions of intermediate steps toward a solution. The model imitates the methodical approach producing big gains on word problems and common-sense reasoning. One benefit is that more computation can be performed in proportion to the difficulty of the problem. (Wei, Wang, et al. 2022)

Taking the idea a step further, Tree-of-thoughts (Yao et al. 2023) asks the model to generate multiple candidate next steps given the current progress toward a solution. At each step, the model evaluates the partial solution and continues down promising paths or backs out of disappointing ones. Tree-of-thoughts is essentially a heuristic search algorithm with the LLM playing the role of the heuristic, which neatly links neural AI with techniques from classical AI.

Sparks of AGI

One of the most provocative papers on LLMs comes from Microsoft Research (MSR). “Sparks of Artificial General Intelligence” (Bubeck et al. 2023) is an attempt qualitatively assess GPT-4’s intelligence using tools from psychology.

The MSR researchers probed GPT-4 along several dimensions, finding good performance on reasoning, problem solving, abstract thinking, and comprehension of complex ideas. They find planning to be an area of weakness and, while the model is very able to learn in-context, there is no means to retain new information for future use.

The paper comes to the relatively safe conclusion that GPT-4 is “a significant step towards AGI” that cannot be dismissed as just statistical pattern matching. Detractors note that as a major investor in OpenAI, the company behind GPT-4, Microsoft is hardly impartial.

“The ‘Sparks of A.G.I.’ is an example of some of these big companies co-opting the research paper format into P.R. pitches,” said Maarten Sap, a researcher and professor at Carnegie Mellon University. (Metz 2023)

Limitations

Before LLMs are put to work in critical systems, there are some fairly serious limitations that will have to be addressed. The most serious is hallucinations. LLMs are prone to stating incorrect information with apparent confidence. Better qualification of uncertainty is needed. Also, LLMs are sensitive to their inputs. Rephrasing a question can lead to very different answers.

LLMs lack a means of integrating new information into an existing model. LLMs make productive use of in-context learning, but when the session ends, that knowledge is gone. There’s no means to move the context, the model’s short-term memory, into the weights of the model. In some sense, LLMs are stuck in time at the point where their training data cuts off.

Also, next-word generation imposes a sequential order that is impedes thinking ahead or planning. Once a token has been sampled it becomes context for following tokens. The model therefore becomes committed to a path which might later turn out to lead nowhere. LLMs have no inner monologue. Instead, tricks of prompting are required to elicit reason, revision, and critical thinking. Interestingly, prompt hackery points out many of the shortcomings of present LLMs, but might also point to fruitful directions for future development.

Applications for good and ill

LLMs will find many uses. GitHub’s Copilot writes solid code in a few seconds. Use-cases in medicine are highly anticipated in an environment of barriers to access and rampant provider burn-out. Lower stakes activities like billing, taking notes, catching medical errors, and interacting with patients will come before AIs are trusted to diagnose and prescribe. The educational potential of LLMs is especially intriguing, with the model serving as a personalized tutor. It’s important to note that work is needed on safety and bias before LLMs are ready to make decisions with serious consequences.

According to the leaked “We have no moat” memo (Anonymous 2023), open source language models are rapidly catching up to the frontier. If this turns out to be correct, access to powerful LLMs will be democratized and widely available. But, also, AI without safeguards will be readily available to hostile powers and bad actors.

Powerful tools falling into malicious hands is a more immediate problem than the emergence of a rogue AI (Bengio 2023) in the mold of Skynet. Scammers and political manipulators will be only too happy to use LLMs to further their ends. AI generated junk content is already flooding the internet, invariably peppered with ads. If the search engines can’t stay ahead, we can look forward to quality content retreating behind paywalls or drowning in a sea of cheaply generated clickbait.

The flip side is that the smartest models may be those trained on ever larger and more power-hungry compute clusters and on the highest quality documents and data, for which rights holders will want to extract payment. The cost-performance curve for future models might bend sharply upward making access prohibitive. In competitive environments like corporate strategy, financial markets, and geopolitics, winner-take-all dynamics might lead to further concentration of wealth and power.

How the distribution of empowering and disempowering effects plays out remains to be seen, but there is reason for concern. Industrial automation has been unkind to the blue-collar worker. Skilled professions form the bedrock of middle-class wealth and power. If a large proportion of intellectual work can be done by AI, that foundation is in trouble.

Conclusion

As a student, I can remember being told that any problem in computer science could be solved by a sufficiently large lookup table. And also that, “All problems in computer science can be solved by adding another level of indirection,” which is sometimes jokingly called the Fundamental Theorem of Software Engineering. In a way, large language models combine these principles. With billions of parameters, an LLM is a very large lookup table. But, it’s doing the lookup indirectly in magical high-dimensional latent space. The prompt is a path to a region of a semantics-encoding manifold. The decoder returns a weighted average of the training documents that shaped that part of the manifold - what Ted Chiang called a “blurry JPEG of the web” (Chiang 2023).

Because the tools of reason are not many, maybe look-up in latent space is enough to simulate reasoning. Or maybe it is reasoning. Are humans doing anything different? One of the defining features of the history of neural AI is that practice has always run ahead of theory. The debate about whether artificial intelligence is real will likely continue long after the AIs have taken over running the world.

Concepts like reason and intelligence remain stubbornly ill-defined. We’re left with “I’ll know it when I see it”, but will we? Are we being fooled like Blake Lemoine, the Google engineer who began to wonder whether that company’s chatbot had achieved sentience? AI godfather Yann LeCun wrote a piece with philosopher Jacob Browning (Browning and LeCun 2022) which contains the memorable line, “deceiving humans isn’t very challenging; we see saints in toast.” Perhaps we’ll know that AIs have finally surpassed us when they start asking whether human intelligence is nothing more than a jumble of evolutionary hacks and cheap parlor tricks.

References

- Anonymous. 2023. “We Have No Moat”.

- Bengio, Yoshua. 2023. “How Rogue AIs May Arise”.

- Brown, Tom B., Benjamin Mann, Nick Ryder, Melanie Subbiah, Jared Kaplan, Prafulla Dhariwal, Arvind Neelakantan, et al. 2020. “Language Models Are Few-Shot Learners”. ArXiv abs/2005.14165.

- Browning, Jacob, and Yann LeCun. 2022. “AI and the Limits of Language.” Noema.

- Bubeck, Sébastien, Varun Chandrasekaran, Ronen Eldan, John A. Gehrke, Eric Horvitz, Ece Kamar, Peter Lee, et al. 2023. “Sparks of Artificial General Intelligence: Early Experiments with GPT-4”. ArXiv abs/2303.12712.

- Chiang, Ted. 2023. “ChatGPT Is a Blurry JPEG of the Web”. The New Yorker.

- Fu, Zihao, Wai Lam, Qian Yu, Anthony Man-Cho So, Shengding Hu, Zhiyuan Liu, and Nigel Collier. 2023. “Decoder-Only or Encoder-Decoder? Interpreting Language Model as a Regularized Encoder-Decoder”. ArXiv abs/2304.04052.

- Hoffmann, Jordan, Sebastian Borgeaud, Arthur Mensch, Elena Buchatskaya, Trevor Cai, Eliza Rutherford, Diego de Las Casas, et al. 2022. “Training Compute-Optimal Large Language Models”. ArXiv abs/2203.15556.

- Kaplan, Jared, Sam McCandlish, T. J. Henighan, Tom B. Brown, Benjamin Chess, Rewon Child, Scott Gray, Alec Radford, Jeff Wu, and Dario Amodei. 2020. “Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models”. ArXiv abs/2001.08361.

- Karpathy, Andrej. 2023. “State of GPT”.

- Metz, Cade. 2023. “Microsoft Says New A.I. Shows Signs of Human Reasoning”. New York Times, May 16, 2023.

- OpenAI. 2023. “GPT-4 Technical Report”. ArXiv abs/2303.08774.

- Ouyang, Long, Jeff Wu, Xu Jiang, Diogo Almeida, Carroll L. Wainwright, Pamela Mishkin, Chong Zhang, et al. 2022. “Training Language Models to Follow Instructions with Human Feedback”. ArXiv abs/2203.02155.

- Ruder, Sebastian, Matthew E. Peters, Swabha Swayamdipta, and Thomas Wolf. 2019. “Transfer Learning in Natural Language Processing”. North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Sutskever, Ilya, and Jensen Huang. 2023. “Fireside Chat with Ilya Sutskever and Jensen Huang: AI Today and Vision of the Future”.

- Vaswani, Ashish, Noam M. Shazeer, Niki Parmar, Jakob Uszkoreit, Llion Jones, Aidan N. Gomez, Lukasz Kaiser, and Illia Polosukhin. 2017. “Attention Is All You Need”. NIPS.

- Wei, Jason, Yi Tay, Rishi Bommasani, Colin Raffel, Barret Zoph, Sebastian Borgeaud, Dani Yogatama, et al. 2022. “Emergent Abilities of Large Language Models”. Trans. Mach. Learn. Res.

- Wei, Jason, Xuezhi Wang, Dale Schuurmans, Maarten Bosma, Ed Huai-hsin Chi, F. Xia, Quoc Le, and Denny Zhou. 2022. “Chain of Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models”. ArXiv abs/2201.11903.

- Yang, Sherry, Ofir Nachum, Yilun Du, Jason Wei, P. Abbeel, and Dale Schuurmans. 2023. “Foundation Models for Decision Making: Problems, Methods, and Opportunities”. ArXiv abs/2303.04129.

- Yao, Shunyu, Dian Yu, Jeffrey Zhao, Izhak Shafran, Thomas L. Griffiths, Yuan Cao, and Karthik Narasimhan. 2023. “Tree of Thoughts: Deliberate Problem Solving with Large Language Models”. ArXiv abs/2305.10601.