The 14th Century

A Distant Mirror: the Calamitous 14th Century by Barbara W. Tuchman has as its subject the “downward slope of the Middle Ages”. The calamities that beset Europe were many. Plague reduced the population by a third. The Hundred Years War resisted all attempts at a settlement. Kings went mad and were usurped by scheming rivals. The Turks relentlessly gained ground at the far edge of the Christian world.

The genesis of this book was a desire to find out what were the effects on society of the most lethal disaster of recorded history[…] Given the possibilities of our own time, the reason for my interest is obvious. The answer proved elusive because the 14th century suffered so many “strange and great perils and adversities” The four horsemen of St. John’s vision, […] had now become seven—plague, war, taxes, brigandage, bad government, insurrection, and schism in the Church.

After the experiences of the terrible 20th century, we have greater fellow-feeling for a distraught age whose rules were breaking down under the pressure of adverse and violent events. We recognize with a painful twinge the marks of “a period of anguish when there is no sense of an assured future.”

Tuchman’s most famous works, The Guns of August and Proud Tower on the WWI era, echo the theme of social order coming undone. In the Distant Mirror of the 14th century, Tuchman sees reflected the calamities of the 20th century. Her book is exactly what history should be - full of wisdom, humor, and lessons our species never seems to learn.

Themes:

- The belief of the Nobility in their own superiority in spite of decadence and failed military adventures

- The venality of the church

- Ever-increasing taxation of the common folk to pay for noble and clerical extravagance

- The weakness of Kings in both France and England

- The persecution of the Jews

- disunity of society

- failed peasant uprisings

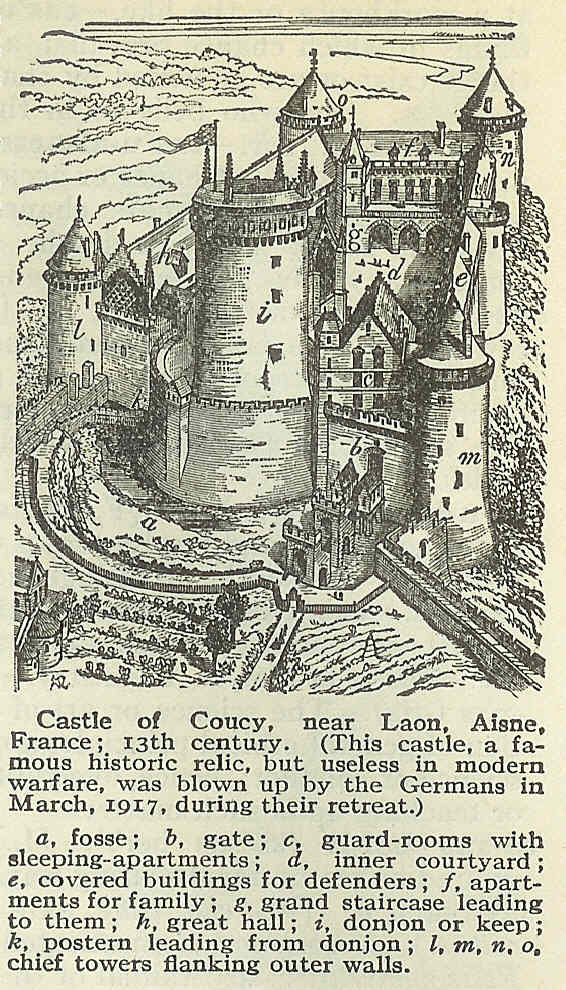

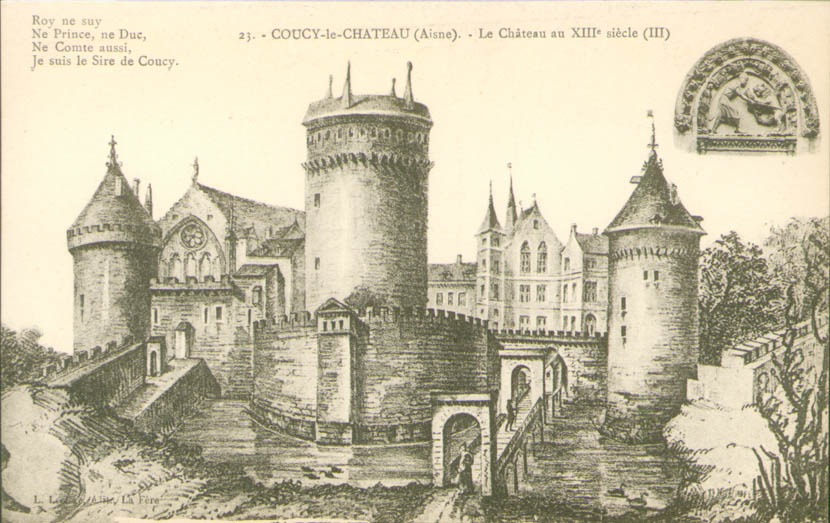

Coucy

Tuchman’s historical narrative centers around the life of Enguerrand de Coucy VII (1340-1397), last of a great dynasty and “the most experienced and skillful of all the knights of France.” Having close relations with the sovereigns of both France and England, Coucy was central to diplomacy between them, as well as figuring prominantly in squables among the fractious French nobility, French designs in Italy, and a disasterous crusade.

Those who pray, those who fight, and those who work

The tripartite social order of the middle ages is described in terms of three estates: the Clergy (First Estate), Nobility (Second Estate), and the peasantry (Third Estate) - those who pray, those who fight, and those who work.

[ ]

]

The 14th century was a time in which the organizing principles of medieval society were breaking down. The sense of the decline of Christendom was pervasive. The Plague could only be devine punishment. The clergy were corrupt, the ruling class stabbing each other’s backs, the knights dedicated to debauchery and unable to defend the realm. All were living lavishly at the expense of the peasants.

During lulls in the fighting with the English, French knights with little to keep themselves occupied turned to banditry. They looted their own country and threatened the towns who paid ransoms to be left in peace. This was such a widespread problem that Crusades and foreign wars were instigated for the expressed purpose of getting rid of the companies of mercenaries. The French fighters seemed, to the common people, no better than the invaders.

Forshadowing Protestantism

The sale of indulgences and church appointments eroded the authority of the Church. Clergy amassed great wealth and kept mistresses. The Western Schism between 1378-1418 did still more damage. Though it would not be until 1517 that Martin Luther nailed the 95 Theses to the church door, the makings of the Protestant Reformation were already taking shape.

Oxford theologian John Wyclif, denounced the sale of indugences and preached the disendowment of the temporal property of the Church and the exclusion of the clergy from temporal government. His followers produced an English translation of the Bible.

Gerard Groote founded a sect known as the Brethren of the Common Life in the small trading towns in the of marshlands of northern Holland—as if only in a remote corner of strife-torn Europe could fresh piety find a place to sprout.

The school of the Common Life in Deventer produced Thomas a Kempis, who wrote a widely read book, The Imitation of Christ, on the theme that “the world is delusion and the Kingdom of God is within; salvation lies in the abnegation of earthly desires; that to desire anything is to be “straightway disquieted”; that man is but a pilgrim in life, the world is an exile, home is with God.

At the same time, Popes repeatedly tried and mostly failed to organize resistance to the advance of the Ottomans, notably the Battle of Kosovo in 1389 and the fall of Constantinople in 1453 that ended the Byzantine Empire.

War and taxes

The noblity needed war to justify their existence, settle their quarrels and fill their coffers. The costs fell on the working classes, without regard to the opposition and resentment engendered.

“It should be an established principle,” wrote Villani, “that war ought not to be paid for out of the purses of the poor but rather by those to whom power belongs.”

Poet Eustache Deschamps wrote “This grain, this corn, what is it but the blood and bones of the poor folk who have ploughed the land?Wherefore their spirit crieth on God for vengeance. Woe to the lords, the councillors and all who steer us thus, and woe to all who are of their party, for no man careth now but to fill his bags.”

The Tailor of Orléans

On hearing of Anjou’s death, a tailor of Orléans named Guillaume le Jupponnier, when “overcome with wine,” burst into a tirade in which can be heard the rarely recorded voice of his class.

“What did he go there for this Duke of Anju, down there where he went. He’s pillaged and robbed and carried off money to Italy in order to conquer another land. He is dead and damned. And the King sent Louie, too like the others.

Filth, filth of a King and a King! We have no King but God. Do you think they got honestly what they have? They tax me and re-tax me and it hurts them that they can’t have everything we own. Why should they take from me what I earn with my needle? I would rather the King and all kings were dead than that my son should be hurt in his little finger.”

The Tree of Battles

Honoré Bonet’s The Tree of Battles was an examination of the laws and customs of war and, inevitably, of its moral and social effects. His purpose in writing the book, Bonet stated, was to find an answer to the “great commotions and very fierce misdeeds” of his own time. His conclusion was blunt. Stated in the form of a question—“Whether this world can by nature be without conflict and at peace?”—his answer was, “No, it can by no means be so.”

He is “heart-stricken to see and hear of the misery inflicted on poor laborers … through whom, under God, the Pope and all the kings and lords in the world have their meat and all their drink and clothing.”

“All husbandmen and plowmen with their oxen when they are carrying on their business” and any ass, mule, or horse harnessed to a plow should have immunity “by reason of the work they do.” The reason was fundamental: security of the laborer and his beasts benefits all because they work for all. Bonet reflected the growing dismay at the “great grief and discord” caused by daily violation of this principle.

With no illusions about chivalry, Bonet wrote that some knights were made bold by desire for glory, others by fear, others by “greed to gain riches and for no other reason.”

Like other prophets, his fate was to be honored—and ignored.

Peasant uprisings

The Jacquerie was a popular revolt by peasants that took place in northern France in the early summer of 1358 which was suppressed by the nobility led by Charles the Bad of Navarre.

In England, the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 resulted from resentment over taxes to pay for military campaigns in France and over attempts to freeze wages at pre-plague levels. Workers, artisans and village officials, rose up in protest and burned tax records.

The maillotins revolt of 1382 was named for the large iron mallets used as weapons by the mob to attack the wealthy, tax collectors and Jews.

Flemish trades people revolted in 1323 and again in 1339, a rebellion which the French helped to crush in 1382.

The wave of insurrection passed, leaving little change in the condition of the working class. Inertia in the scales of history weighs more heavily than change.

Tuchman compares the coronation of Isabeau of Bavaria as Queen of France in 1389 to a Roman circus. What is government but an arrangement by which the many accept the authority of the few? Circuses and ceremonies are meant to encourage the acceptance; they either succeed or, by costing too much, accomplish the opposite.

Pessimism

On the downward slope of the Middle Ages man had lost confidence in his capacity to construct a good society.

The scholar Jean Gerson believed he lived in the senility of the world when society, like some delirious old man, suffered from fantasies and illusions.

End and New Beginning

Enguerrand de Coucy died in captivity in 1397 after the allied Crusaders met defeat at the Battle of Nicopolis at the hands of the Ottoman forces of Bayezid I.

Byzantium fell in 1453. The Gutenberg Bible was published in 1455. The Council of Constance, which lasted from 1414 to 1418 ended the Western Schism.

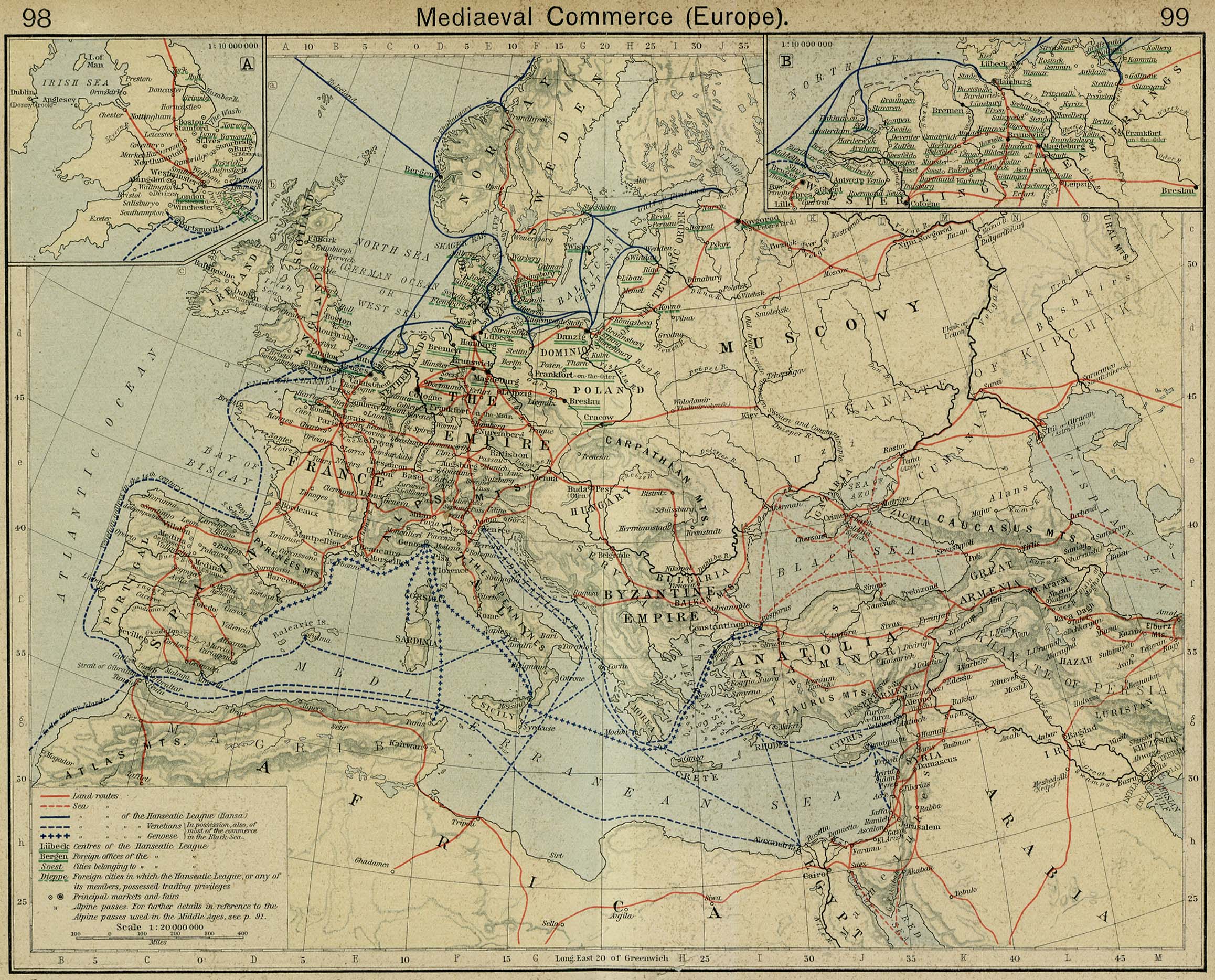

Europe’s merchant shipping network grew throughout the Middle Ages, setting the stage for the Age of Discovery.

The ills and disorders of the 14th Century could not be without consequence. Times were to grow worse over the next 50-odd years until at some imperceptible moment by some mysterious chemisty, energies were refreshed, ideas broke out of the mold of the Middle Ages into new realms and humanity found itself redirected.

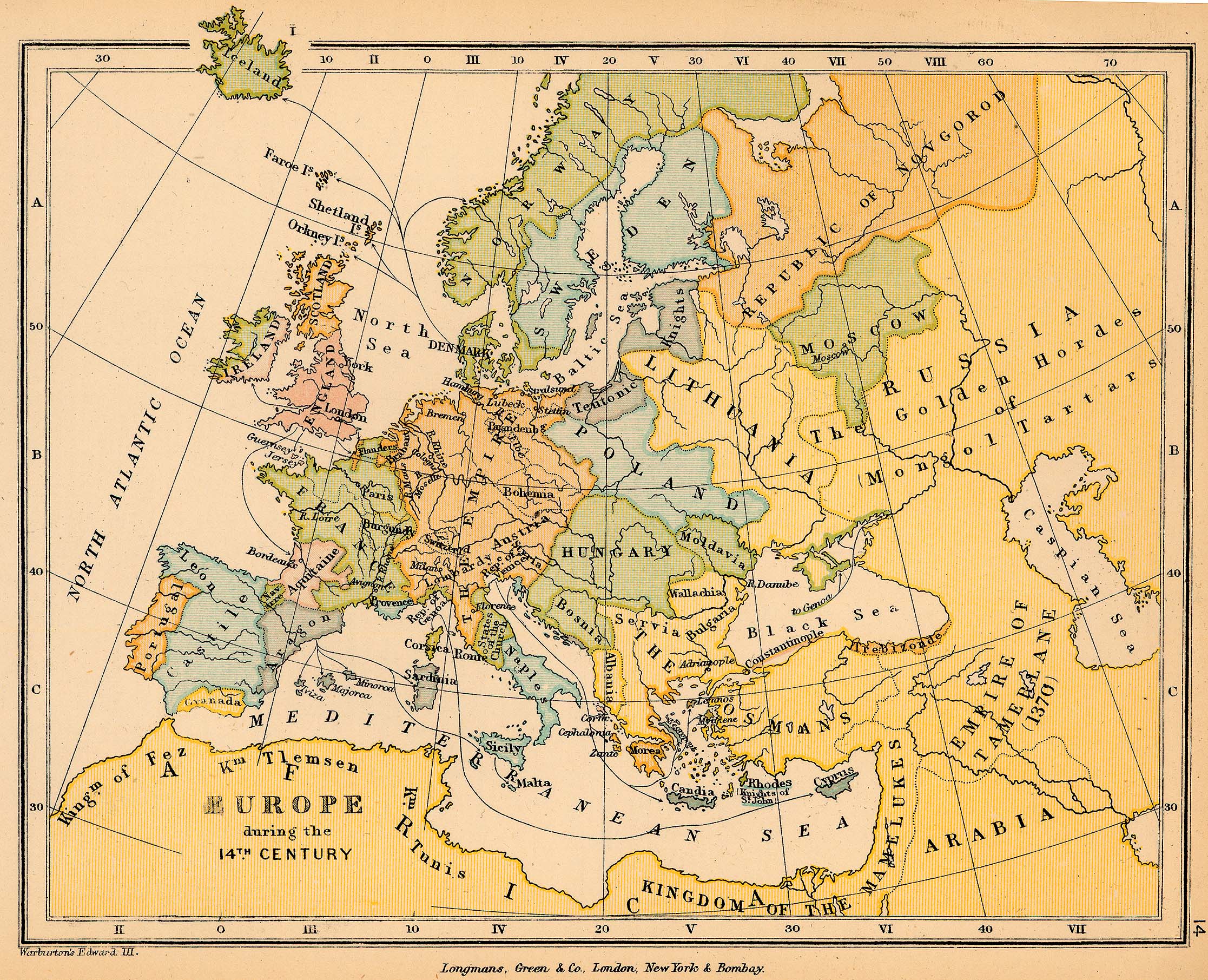

[Insets: England; Hanseatic League in Northern Germany]. From The Historical Atlas by William R. Shepherd, 1926.

[Insets: England; Hanseatic League in Northern Germany]. From The Historical Atlas by William R. Shepherd, 1926.